In the early years of the Dutch revolt, the Spanish duke of Alba tried to stamp it out.

He had successfully besieged and taken Haarlem and Naarden, but his cruel treatment of the population only hardened the resolve of the other cities.

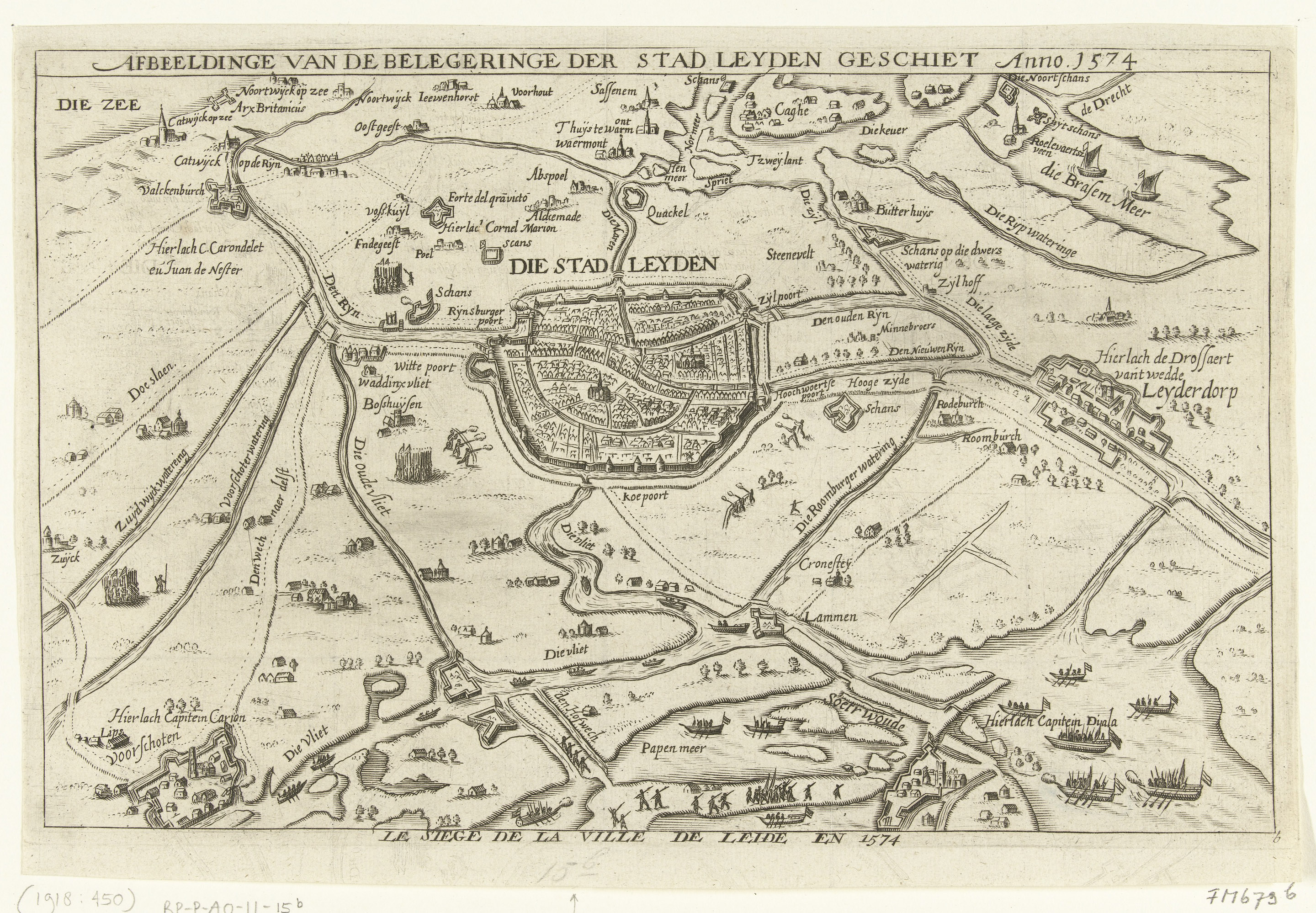

Alkmaar was the first to withstand an attack and in the autumn of 1573 CE Alba switched his attention south, to Leiden.

The city was garrisoned by some 11,000 troops, mostly foreign mercenaries.

It had anticipated an attack and was well provisioned.

Its defenses were solid and the 15,000 Spanish, who tried to dig trenches to bring their artillery close to the walls, had much difficulty with the loose soil.

In the next year Louis of Nassau tried to relieve the city.

In the Battle of Mookerheyde the Spanish proved the stronger party and repelled the counterattack.

The diversion of the Spanish attention allowed Leiden a brief respite.

However the citizens, who had grown overconfident, neither strengthened the garrison nor restocked their supplies.

Also, they did not destroy the Spanish redoubts from the first siege.

When the Spanish army returned and once more laid siege, the city folk were hard pressed.

Instead of preparing to breach and assault the walls, the besiegers adopted a strategy of waiting and starving the citizens.

William the Silent, leader of the revolt, wanted to break the dikes and flood the countryside, so that a fleet could bring relief.

That would cause tremendous damage to the land and at first the people refused to carry out the plan.

But when hunger grew, they changed their minds.

It took time for the sea to flood the land and William the Silent fell ill, but after some delay the fleet started working its way up from the south,

occasionally battling the Spanish at choke points.

The going was difficult, because the water was of course shallow and the ships depended on the wind coming from the right direction.

The citizens of Leiden, now famished and weakened, started to succumb to disease and were about to surrender.

During the second siege the city lost 1/3 of its total population of 18,000.

The only things that had the defenders hang on were the memory of the fate of other cities that had surrendered and the staunch resistance of the city council.

The water weakened a section of the walls of Leiden, bringing it down with a crash and leaving it open for assault.

But the Spanish thought that the sound meant that the Dutch were breaking another dike to increase the flood.

Already increasingly isolated on small islands, they did not investigate but abandoned the siege.

More than four months after the start of the second siege, the fleet reached the city and brought herring and white bread.

The successful defense was a boost for Leiden, which got a university a year later.

The Spanish army, which had not received pay for a long time, mutinied and withdrew south,

though the war was far from over.

War Matrix - Siege of Leiden

Age of Discovery 1480 CE - 1620 CE, Battles and sieges